In a Tiny Japanese Town, Artisans Are Crafting Some of the Best Turntable Needles on Earth

JICO is a 150-year-old company that's keeping vintage record players alive, one handcrafted stylus at a time.

One day in December, during a tour of the manufacturing company JICO in Hamasaka, Japan, I watched the 77-year-old master craftsman Kotaro Morita carefully carve a piece of hard-to-find black persimmon wood the size of an incense stick into a centimeter-long shaft. He was making a turntable needle called Kurogaki, which he originally designed in his free time before JICO started selling them in 2019. Each turntable needle the company produces is made by hand.

Kazushi Nakagawa and Ray Nakagawa, the father-son duo who serve as JICO’s executive director and chairman, watched Morita work alongside me and explained the production process with reverence. In the next room, another worker affixes the wooden needle with a diamond tip, at which point it becomes a full turntable stylus. Each needle is then tested for imperfections by sound checking them on a record by Sayuri Ishikawa, who’s been recording in the traditional-inspired Japanese style of enka for a half century. Then they’re sent to DJs and audiophiles around the globe.

JICO fills a unique role in the world of audio equipment: They’re essentially turntable needle archaeologists, reproducing discontinued needles so that music listeners can continue using vintage record players. Though the 13 people, including Morita, who work in the company’s turntable needle division also make original models like the Kurogaki, their main job is to reverse-engineer proprietary needles that have long gone out of production. If you’ve ever replaced a needle for an old turntable you found at a garage sale, odds are you purchased one of JICO’s handmade clones.

JICO’s walls are lined with 2,000 different models of needles that they’ve recreated, but the company’s trajectory changed in 2018 thanks to one needle in particular: the Shure N-447, a discontinued favorite of hip-hop DJs, which JICO revived from the dead. This is the needle that transformed the company from a niche parts supplier to a household name in the world of vinyl DJs.

Now, just months before 28 million visitors begin to descend on Osaka for the World Expo 2025, JICO is hoping to attract that newfound audience to the tiny, far-flung town of Hamasaka to experience a listening room where guests are encouraged to bring their own vinyl for a two-and-a-half-hour private session on one of the finest hi-fi systems in the country. The idea is that those visitors will not only listen to recorded music in its purest form, but also do their part to spare the city from the dangers of extinction that is facing so much of small-town Japan.

Hamasaka sits 190 kilometers northwest of the tourist magnet Kyoto, along the coast of the Hyogo prefecture. Historically, its economy was based on sewing needle production: In the Edo period, 80 percent of the town’s population worked on sewing needles, a makeshift assembly line of materials passed between homes. JICO carried on that sewing needle tradition when it was officially incorporated as Nippon Precision Jewel Industry Co., Ltd., in 1873, four years before Edison invented the phonograph.

As of 2022, just 12,814 people live in Hamasaka and its neighboring town of Onsen. It takes at least four hours to reach Hamasaka from Kyoto through a combination of trains and buses, and I was warned several times that snow might make traveling there impossible. (The region confounds Google Maps, and if you don’t triple-check your itinerary, you might end up in the wrong hotel 60 kilometers away, like me.)

When I finally arrived at 9 a.m. on a Monday, the only two open businesses were a secondhand clothing store (with no shopkeeper) and a quaint cafe. “A lot of people grow up here until high school, then leave for college and go to other jobs,” Ray Nakagawa said. At 28 years old, he’s a rare example of someone who returned to continue the family business. Most others don’t come back.

In 1949, JICO began pivoting from sewing needles to turntable needles. When those went out of fashion in the late ’80s, they shifted to VHS and CD cleaning products, along with other manufacturing tools. By the early 2000s, JICO reinvested in the needle side of the business with an online storefront, years before both vinyl’s comeback and the explosion of online retail.

Ray poured me some sake as he recounted the company’s history, translating for his father Kazushi and uncle Yukihiro Nakagawa, who serves as JICO’s president. (Ray’s mother, Miwako, helps on the management side.) We were also briefly joined by 42-year-old Takao Oku, who used to craft guitars for metal-centric manufacturer ESP in Tokyo before returning to his hometown to make needles beside Morita. Oku’s favorite musician is Ozzy Osbourne, and he looks like he can shred.

Although vintage recreations had long been JICO’s specialty, the company has made a fundamental shift to producing primarily the Shure N-447. Like most DJs, this is the product that introduced me to JICO. Designed in the 1960s, Shure’s M-447 cartridges (and N-447 styli) became an industry standard due to their affordability, high tolerance for scratching, and bass presence. In 2018, when news broke that Shure was stopping the stylus’ production, a friend of mine hoarded as many as he could buy.

JICO had already been selling replacement needles for the Shure model, but there weren’t any companies making the full cartridge, which houses the needle. So if you didn’t already own one, you never would. It was a moment that JICO was waiting for. “We said, ‘We might as well just make them ourselves,’ Ray recalled. “From that point on, we spent about three years in production and R&D. It was a huge motivation for us.”

The N-447 clones began appearing on sites like Turntable Lab and Juno around 2021, and word about JICO spread. Meanwhile, the ongoing COVID pandemic left many people sitting in their living rooms and thinking about how they could improve their home hi-fi setup. And over the last couple of years, Japanese-style listening bars popped up in many major cities in America. As Japan once again started welcoming tens of millions of tourists to the country post-pandemic, JICO began taking reservations for tours of their headquarters.

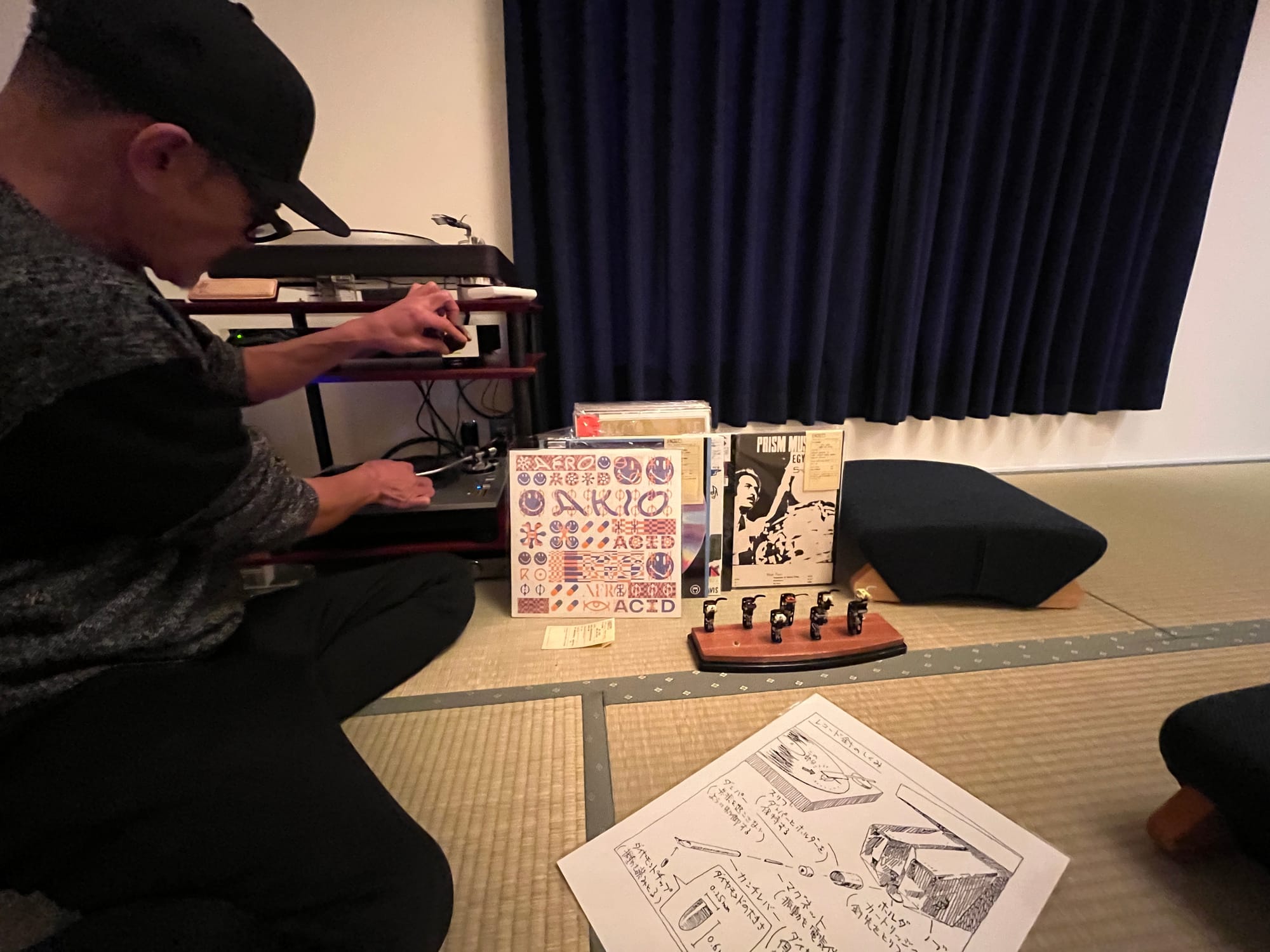

Since Hamasaka isn’t a town you’ll find on any tourist itinerary, their strategy includes a stepping stone to entice people to make the trek; JICO partnered with Feel Records in Kyoto to show off some of their wares. Located along a busy thoroughfare, the business includes a record store, cafe, and private listening loft. When I visited it a few days before making my way to Hamasaka, I picked out a stack of records to listen to and handed them to the veteran Japanese turntablist DJ Shark, who is working with JICO. He asked that I take off my shoes, led me up a rickety ladder to a tatami mat room, and played records on a hi-fi turntable one-by-one, choosing different needles based on the genre: black persimmon for higher frequencies in the Egyptian jazz of Prism Music Unit, M-447 for the heavy low end of California agitprop greats the Coup. When the bass on the Coup’s 1994 track “Takin’ These” hits, Shark nods and breaks out of Japanese to say: “Baaaay Areaaaa.”

It’s free to preview a couple records at Feel, but the full JICO headquarters experience isn’t cheap. The tour costs 25,000 yen ($160), which includes a chef-prepared lunch of local seafood with tea or sake service, firsthand view of the production process, and a few uninterrupted hours with two distinctly awesome hi-fi systems. I listened to a few Japanese and international selections from their in-house collection: Tatsuro Yamashita “Turner’s Gondola,” Masayoshi Fujita “Moonight,” Michael Jackson’s “Can’t Help It” (a favorite of Kazushi), and Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports (a favorite of mine). What I noticed most about hearing the Eno album on the system wasn’t the ethereal loops, but rather the spaces in between them. Heavenly traces of reverb floated like fog around the vocal harmonies, while the ARP 2600 synthesizer sounds were trailed by resonant echoes that folded into stunning silence.

“The concept is not just for people to see our open factory, but for them to enjoy the time they spend listening to music that is produced through our needles,” said Ray. “Listening to the music while you eat, reading a book while music’s blasting out—we want you to fully embrace the music and the moment.”

JICO’s hi-fi systems rivaled all the best-sounding listening bars I visited in Japan—including Studio Mule in Tokyo, Music Bar Beatle Momo in Kyoto, and Bar Jazz in Osaka—and reminded me that a hi-fi system can fundamentally change how one thinks about music.

As for whether the investment will pay off for JICO, that’s yet to be seen. In a sense, business is booming. At January’s National Association of Music Merchants trade show in Anaheim, California, they announced a partnership with Korg, providing the cartridges and needles for the new portable Handytraxx Tube J turntable, with the JICO name noted prominently in the marketing materials. The N-447 continues to gain popularity, with 20,000 produced in 2024. However, that doesn’t come close to a competitor like Denmark-based Ortofon, which annually sells half a million DJ needles. Ray was mum about how many visitors have booked a tour so far, and my impression was that tickets weren’t exactly selling out yet.

The hope is that visitors will come to Hamasaka and invigorate the local economy, which now revolves primarily around fishing. Maybe the town becomes a little more attractive for young people like Ray to stick around and continue their families’ businesses or start new ones (a record shop with a comprehensive Black Sabbath section, perhaps). The same craftsmanship that kick-started Hamasaka’s original needle industry might just be what reinvigorates it. Almost no one I met in Japan had yet heard of the town of Hamasaka—but every vinyl DJ I spoke to knew the name JICO.