Kelly Lee Owens Breaks Down Four Perfectly Produced Albums

From Björk’s ‘Vespertine’ to Depeche Mode’s ‘Violator,’ these are the LP productions that inspire the techno-pop musician most.

The Producers is an interview series where our favorite producers discuss their favorite music production.

Kelly Lee Owens talks about artistic inspiration with the wonder of a mystic. “Without sounding too woo-woo,” she says, “it’s something that’s beyond me.” When she began thinking about what would become her fourth album, Dreamstate, two years ago, a few things flashed in front of her mind’s eye: rave culture, huge hordes of people coming together, and a party-starting neon hue now known as Brat green. “I was getting all these downloads from the universe,” she attests. “It’s your job as an artist to figure out what the hell wants to be said.” This kind of decoding, she adds, can be a key part of the production process, too.

For the Welsh-born, London-based Owens—who makes electronic pop that frays techno’s smooth lines with bulbous analog tones, found sounds, and her own airy vocals—music production is a fluid process that works in concert with writing, mixing, arranging, and just being open to the possibilities around you at any given moment. “Good production puts a spotlight on the emotion you’re trying to convey,” she explains.

With Dreamstate, which was also inspired by the 36-year-old’s life-altering experiences opening for Depeche Mode last year, she wants to convey massive feelings that could reach the last row of a packed stadium. Whereas her previous records could be heady and insular, this one reaches for dance floor nirvana. It’s the type of music that begs to ring out across an endless sea of hands-in-the-air humanity—even the album’s couple of ballads are daunting in scope as they express a bittersweet blend of Jumbotron-sized sadness and hope.

To achieve such a communal sound, Owens ripped herself out of her own bubble and pursued a more collaborative approach. Though she produced her 2017 self-titled debut almost entirely by herself, and her two subsequent LPs were primarily made alongside just one close collaborator each, Dreamstate includes credits from bold names including Tom Rowlands of the Chemical Brothers, the electronic duo Bicep, and the 1975’s George Daniel, whose new label DH2 is also releasing the album.

“There’s this very toxic thing at the moment where, because of the state of the music industry, artists are expected to do everything in electronic production themselves, which I do,” she says. “If you don’t touch it all, especially as a woman, it’s like you’re not the authentic creator of your own music. But no one does anything alone, that’s boring. I’m so tired of it. This is still a Kelly Lee Owens record, and my collaborators helped me facilitate my vision.”

That vision includes plenty of analog sequencers and synths—including the Roland Juno 60, and Sequential’s Pro-One and Prophet-5—which Owens originally fell in love with because of their tangibility and inherent volatility when she started producing music a decade ago. “You can program a sequencer, but if it’s analog, it doesn’t mean it’s gonna actually play what you want it to play,” she says. “Eighty percent of the time it does, but the other 20 percent is where the gold is. There are no mistakes. I remember just getting excited about the fact that something was imperfect, kind of like how I felt about myself.” She smiles and lets out a small, knowing giggle.

At this point, with seven years of singular work and globetrotting gigs behind her, Owens is more confident than ever in her abilities as a writer, singer, performer, and producer. But would she ever consider producing someone else’s album? She seems surprised by the question. “I’ve been scared to do that, because my creative process is so fast and unplanned,” she says. But after some more hemming and hawing, she lands on an answer. “There’s a track on the new Ariana Grande album called ‘We Can’t Be Friends’ that is very Robyn-esque, that she produced with Max Martin—I feel like I could have produced that,” Owens says. “I would love a crack at doing something like that. I grew up with pop music, it’s really deep in me, and I’m only starting to explore it.”

Below, Owens expounds on four of the artists and albums that have inspired her most as a producer.

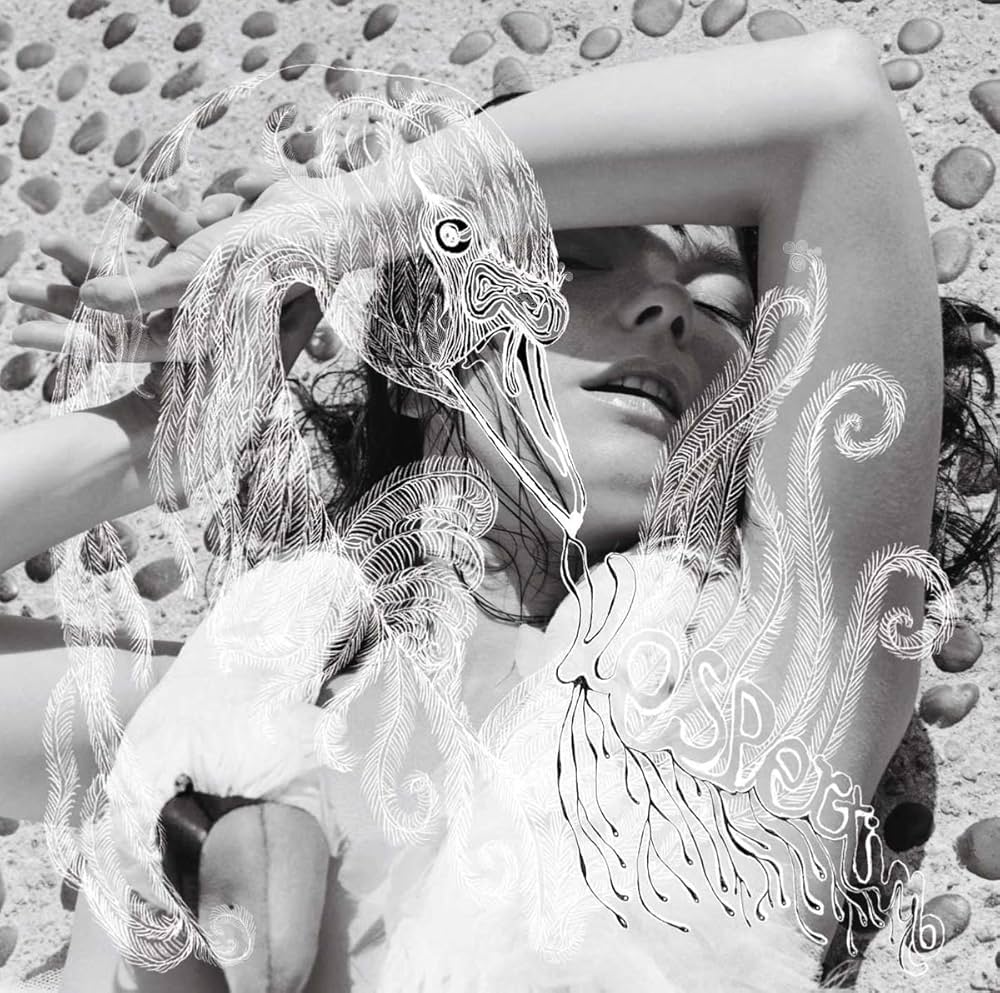

Björk: Vespertine

Producers: Björk, Thomas Knak, and Martin Console

Kelly Lee Owens: I don’t know if my first album would have existed without Vespertine. Just Björk being a female producer, writer, performer, and all-encompassing, godly being. [laughs] That album consists of what she called “microbeats,” made from recording the noises of household items, and my first album has a lot of tiny beats and weird samples from my iPhone on it, because Björk made me feel like it was OK to use whatever means necessary.

The first time I met Björk was when I was working behind the counter at Rough Trade East. What I love about record stores is that they’re so neutral, because you’re all just music fans in there. No one’s on a pedestal. So I remember her coming in—it was around 2011, at the time of Biophilia, because she was wearing that orange wig—and she was like, “Excuse me, where is the techno section?” I didn’t listen to techno that much at the time; I didn’t really get it. The fucking irony!

Then she came to play a Halloween DJ set in the shop with Arca. We had mutual friends in common, so we all went out afterwards. That was when I was mixing my first record, and I had read that alcohol affects your hearing, so I wasn’t going to drink that night. But then Björk handed me a tequila shot with a worm. [laughs] This is my musical mum—I wasn’t gonna say no. So I thought, This must be part of the plan, take these worms and see what happens. I don’t even really like tequila, but if Björk hands you tequila worms, you love them, and you just go for it.

When I was making the song “Anxi.,” from my first album, I remember thinking, What would Björk do? She would swirl things around. She would make it weirder. So I made it weirder. That album came out around the same time as her single “The Gate,” and I went to a launch event for it in London. I brought a copy of my record on vinyl, and I gave it to Björk as a gift—I feel embarrassed about doing that now, but I also love that about myself, that tenacity. A few months later, she did a mix of songs she had been listening to for Mixmag, and she put “Anxi.” on it. I was like, This can’t be real. And then she asked me to remix her song “Arisen My Senses.”

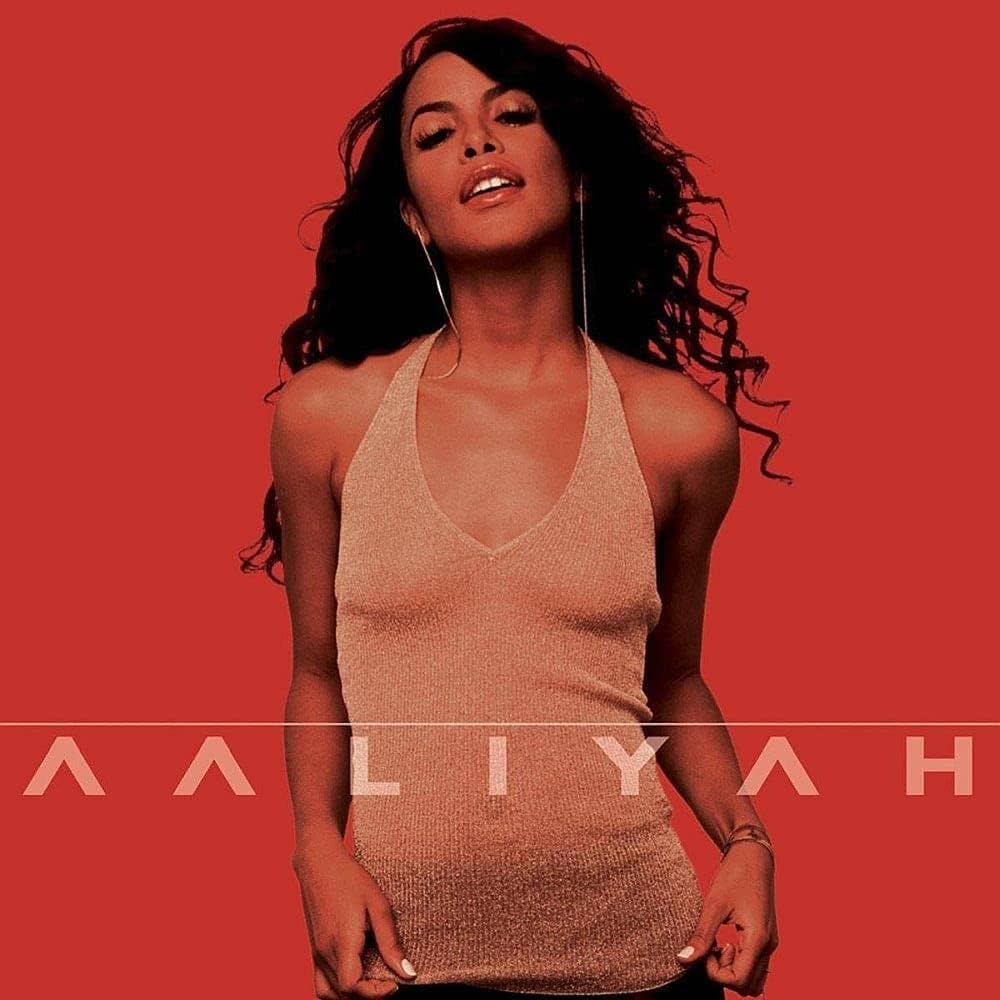

Aaliyah: Aaliyah

Producers: Timbaland, Eric Seats, Rapture Stewart, Bud’da, and J Dub

I was listening to this album this morning. It’s still so innovative, it could have been made yesterday. The production transcends all genres. What I love about Timbaland’s production in particular is the humanness in it—his beatboxing and bringing in things that aren’t rigid and just the breath. Breath is life.

And then there’s his snare sound—I can’t cope. The only other person I can think of who has such a distinct snare sound is Travis Barker. I’m obsessed with drums, and Timbaland’s specific drum sound is mad. I don’t use snares that often because I hate most of them. So if I like a snare, I’m like, Oh my God! I know I can’t record a snare like that myself, so I just don’t really put a snare there, or I make it small. Because if it’s not adding value, it shouldn’t be there.

It’s also about the placement of the drums and everything around them. I actually saw a snippet of Timbaland talking about how, depending on where you put the beat, it can change the intonation of the bass line completely. It’s all melding into one thing, a sum of its parts. It doesn’t need to be complicated, but pushing a rhythm to somewhere it normally doesn’t go can change the song. I’ve realized I’m quite odd in terms of how I hear music—I think about beat patterns and beat placements in a different way. I’ll be like, “No, no, no, the snare’s got to be there.” And someone else is like, “Technically, that’s wrong.” And I’m like, “Well, that’s boring, so we’re gonna do it this way.”

Around my first album, I did a cover of “More Than a Woman” because I grew up listening to that song and thinking, She has the same kind of tone as me, and it’s not this big, belty voice, but it’s still soulful. Maybe I could do that because she’s doing it. Aaliyah has... had… I hate talking about passed people in the past tense. She has a soulful essence, period. And this grace and transcendence. Her voice is quite ethereal, which you don’t often find with that genre. That’s what made her unique.

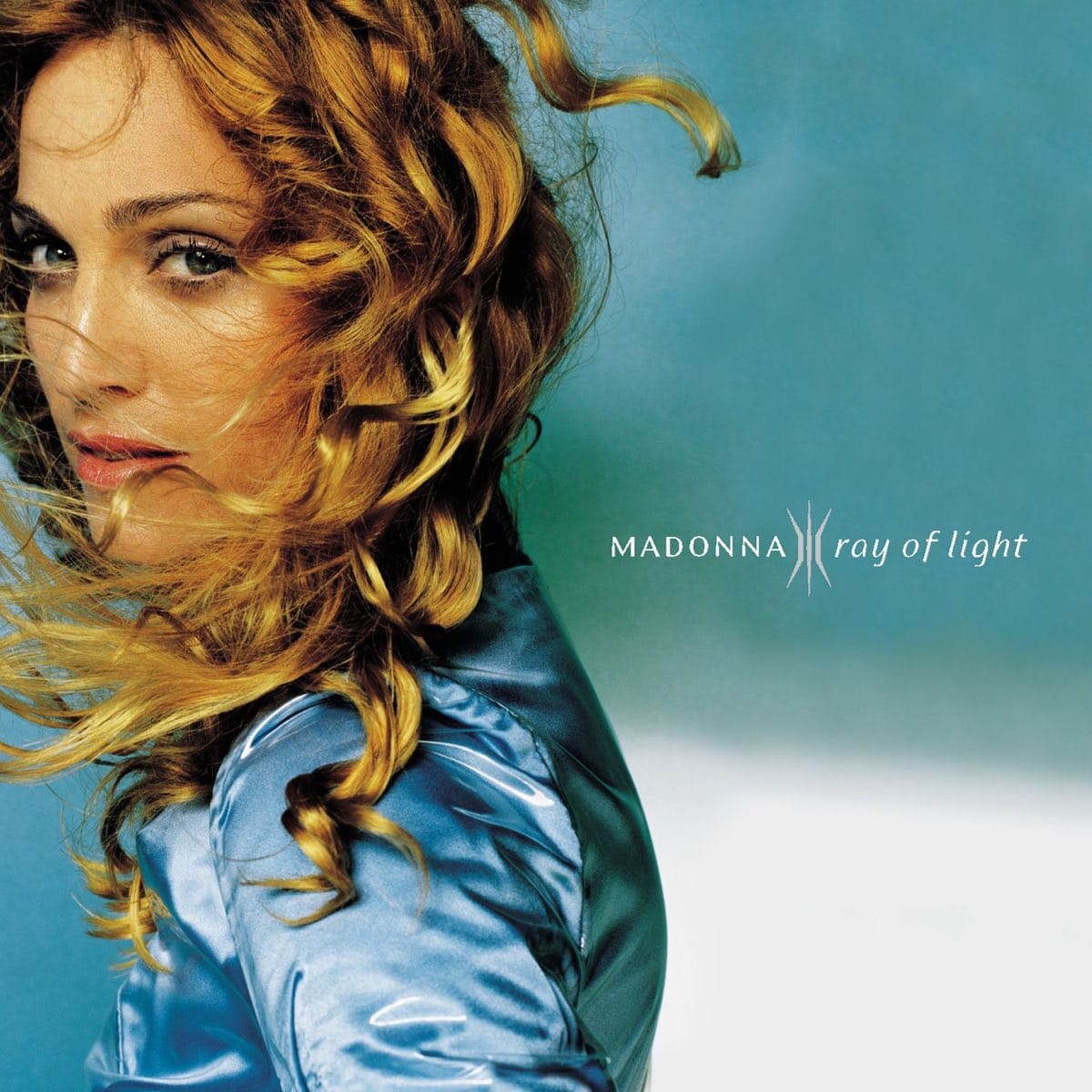

Madonna: Ray of Light

Producers: Madonna, William Orbit, Marius de Vries, and Patrick Leonard

When I heard “Frozen” as a teenager, it blew my mind. I’d never heard anything like it. There’s electronic elements, but also that dark, almost Celtic feel. And the video: Madonna in this gothic dress in a desert?! But at that point I didn’t really listen to the rest of Ray of Light.

Then, when I was thinking about this new record, it was one of the things that was downloading to me: Listen to this album now. I loved the juxtaposition of having such a euphoric title track and the darkness as well. You got bangers and you got ballads. The dark and the light, it’s a perfect marriage for me.

But the main thing telling me this was what I should aim for was that I got to meet William Orbit for lunch last summer. He had just come back to thinking about making music again. He was on Instagram, and I just DM’d him. I was like, “I think we would just work amazingly well together, I love your production.” And he responded.

We were talking about working together, but my timeline was moving so quickly. And it kept coming to me that if I were to work with him, it would probably be for a whole album, which wasn’t going to be possible right then—but try telling 16-year-old Kelly that you’re having lunch with William Orbit but you’re not gonna work with him because the universe is telling you to do something else!

At that lunch, he said that Madonna recorded a lot of the vocals for Ray of Light in one take, because it was on tape. I was like, Oh my God, I need to record in this way. I was telling him how I write the music first and then the lyrics come to me, or I fit them in, and he was like, “But you have to know what you’re gonna say.” It sounds obvious. But it made me think, What do I want to say? How can I cut through all this bullshit and just get to it? That’s where “Trust and Desire” came from.

That song is so different from what I normally do, and it’s the one I worked on the most myself. This is me, bare-bones. This is Kelly. This is a little Welsh girl coming from a traditional folk background. The need was to be really vulnerable. I actually wrote and recorded the demo lyrics for that song in [the actor] Michael Sheen’s house in L.A. He was helping me out by letting me stay there for free, and he’s got a thank you on the album. Without him, I wouldn’t have written some of these songs. And I borrowed a mic from Charli XCX, who lives five minutes away, because I just had to get this down.

I took that demo back to London, where I had this piano, and it was just pulling these chords that I laid on top, really sparse, creating a world. Then I was finding sounds and recording them, whether it’s with a phone or a microphone, and having them come in and out. I’m just building a picture. Then I was like, I know what this needs. It was Raven Bush’s strings—he’s Kate Bush’s nephew. It was so embarrassing—actually, it’s not embarrassing, and I’m going to tell you this, because we’re talking about production—I wrote the string part by recording a voice note of me singing it, and I sent that to Raven. I’m not there notating. It can be as simple as working with someone who’s fucking amazing at playing strings and just singing a part on top of the thing you’ve already created. It doesn’t have to be gatekeeper-y. You find a way.

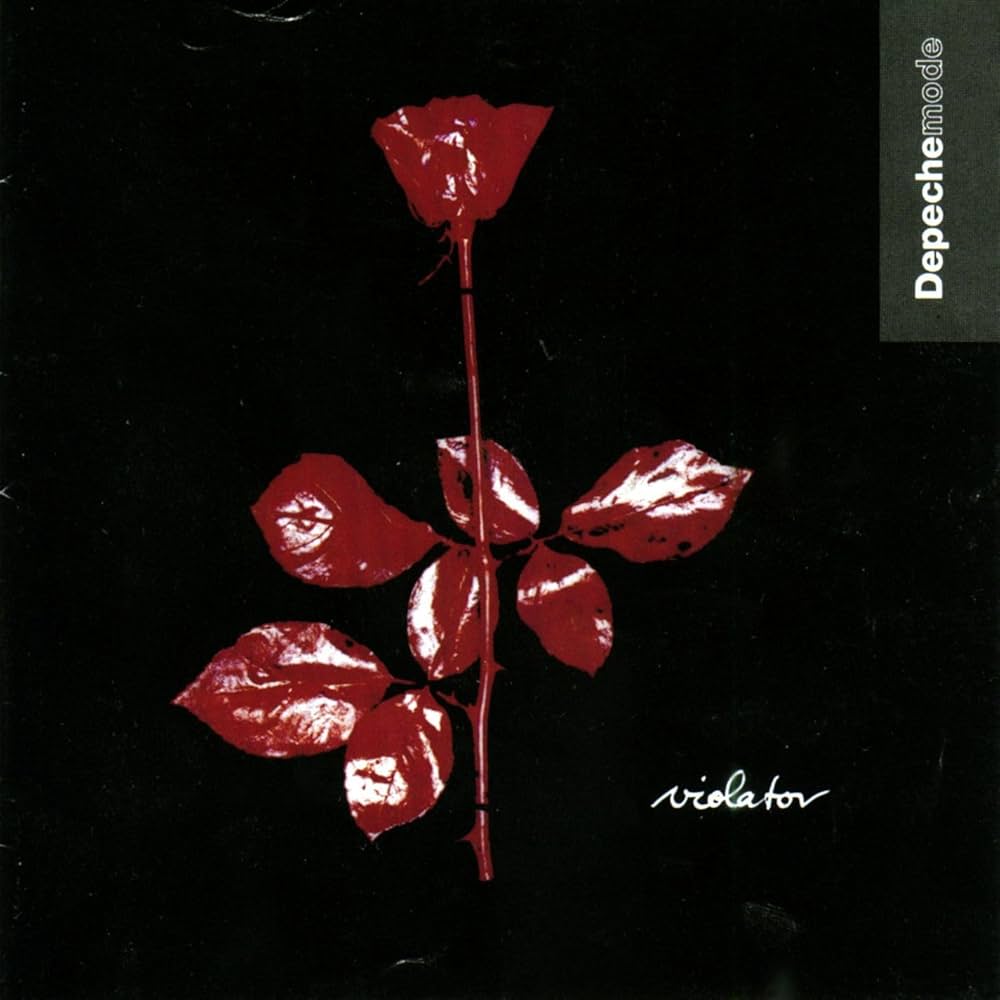

Depeche Mode: Violator

Producers: Depeche Mode and Flood

Touring with Depeche Mode last year was one of the best experiences of my life. I was playing “Lucid,” from my first album, and I had this moment of thinking about me in my bedroom making that song, never dreaming that I would play it to 75,000 people.

It was an intimate experience, too. I remember Dave [Gahan] knocking on my dressing room door: “Welcome to the family.” I got to hang out with Martin [Gore] most nights. He’d come out and watch my set. We had the same resonance on so many things, and it was just so nourishing. Martin and I are friends now, we text. I sent him Dreamstate, and I was so scared about his reaction, but he said it’s so uplifting and joyful. Actually, I was a little bit insecure about one of the songs, not sure if it was good enough, and that was one of his favorites. He gave me that boost of confidence. This is the thing about Depeche Mode: They care. Anyone could support them, but they give platforms to artists that are still on the rise. There were three shows left at one point, and I was just crying every night because I was so sad that it was about to end.

Touring with them made me really understand and appreciate their epic synth lines. There’s something of the transcendent in those parts, which I connect to, though I haven’t perhaps gone there in that anthemic way with my own music yet. There was one point where I got to hear the individual stems for all of Depeche Mode’s hits. I was blown away. On the surface, they’re pop songs, and there’s a simplicity about them. But no. Hearing each individual part made me layer things up seven times on my own music, because it’s about that wall of sound, in a subtle way.

They also inspired me because each of their songs has not just one but five really hooky riffs. That’s not easy, that’s the writing. But then the production is boosting each layer of that with something completely different, something that you would never expect. It’s genius. And then the sound design, things coming in and out, like weird, reversed vocals. When you think you’re safe, something’s gonna come at you. Your mind is constantly surprised and kept on edge. It’s really clever and really hard to do.

When I was playing those shows I hadn’t written this new record yet, and it taught me so much. “Dark Angel” was the first thing I wrote after I came off that tour and it’s very anthemic. When you’re dealing with stadiums, you want to fill the space. I was like, “Let’s just do this. How many people can I connect with?” For me, the more people there are in front of you, the better. If you give me a room full of 50 people, I’d be like, “I’m gonna die!” Whereas with 75,000 people, I’m like, “Yes!”

They played at the O2 in London in January, and their tour manager was like, “There’s someone I want you to meet, Kelly, follow me.” It’s Flood. I’m like, What is going on? I’m watching Depeche Mode next to Flood. Then I got to go to Flood’s studio. He was like, “Go on then, play me three of your demos.” I have never sweated so much in my entire life. One of them was “Ballad,” and he was like, “Yeah, yeah, good. The next one, please.” And then after another track he said to me, “Did you edit your vocals? Chop them up?” And I was like, “Yeah…” He said, “Don’t do that. The best vocal takes I ever got, with people like Dave Gahan and PJ Harvey, was them singing into an SM57 microphone with me sat next to them, giving me a performance.” That was another nugget where I was like, Whoa. And then “Ballad” was recorded in one take. I thought it would be a demo, but it had all the right emotions in it.