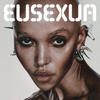

Dance and Sex and Enlightenment Are One and the Same on FKA Twigs’ ‘Eusexua’

The multihyphenate’s new album can’t be untangled from her physicality and her healing.

FKA Twigs has built entire worlds around the fact she is a fascinating dancer, so listening to her music without also watching her choreography can feel incomplete. This is especially true with her third proper album, Eusexua, which feels tailored to the body itself. On “Striptease,” the sub-bass seems designed to ignite a truncal twitch; a cascading tweeter on the Björkian “Room of Fools” sounds like an Ableton cue for a flick of the eyes (an underrated body part in choreography). Eusexua’s thesis is to wrest its listeners into a body high. It might feel like the beat is the source of your elation, but it’s really the life-force inside of you.

In this spirit, here’s a small sampling of dance moves I have performed on instinct while listening to certain Eusexua songs:

- “Perfect Stranger”: booty-tooch; beginner-level pas de bourrée

- “Sticky”: interpretive full-body waterfall

- “Childlike Things”: tiddy shake

The rave is everywhere if the rave lives in your heart, so I have performed these moves in various places: in the elevator of my apartment building, on the New York City subway, in my office chair (as mother instructed), and walking down Delancey, a street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side that I like to call “Club Delulu.” This is what I take as Twigs’ message—not just an assertion of her power and creativity, but the idea that creativity germinates somewhere deep in the gut, and your only recourse is to let it out, unjudged. To that end, she created “The Eleven,” a guided meditation with 11 dancers, as an exhibition last September at Sotheby’s. The self-described “durational artwork” was based on “the 11 pillars of eusexua”—for example “looping,” which refers to “entering a virtuous circle of creative motion where your inspiration comes within you and you’re creating work that reinspires you.” (The numerology is off the chain.) “I now know that life is not beyond my intervention,” she wrote in her artist statement. “It is difficult, but not impossible.” It might sound woo-woo or even a little cultish, but it’s also a foray into self-actualization.

In 1943, the dancer and choreographer Martha Graham famously called the creative impulse “a quickening that is translated through you to action.” Art, she posited, is a method of emergence that, in the moment of its creation, is free from her own critical analysis. It was none of her business, she went on, whether what she made is good or bad art—it just is. This sense of existential freedom pulsed through Graham’s work, in dances that positioned the body in various stages of tension and release, and emphasized a core tenet of immediate response and reaction.

FKA Twigs is so informed by Graham’s legacy that in 2024, she was cast in a solo for the Martha Graham Dance Company’s annual gala. The work she performed was “Satyric Festival Song,” which Graham created as an homage to the Pueblo tradition of jester-like figures, and a way to poke fun at Graham’s own seriousness. The singer posted photographs of the dance’s most iconic pose, with her hands backwards and framing her face like a satyr or an axolotl, the move reflecting both a silly taunt and a slightly intimidating challenge. Like Graham, Twigs may not be immediately perceived as a funny artist in her own work—because innovation can often be mistaken for self-seriousness, and because her lyrics about love and depression can be so emotionally wrought. But she has always had an impish quality about her, even if her humor is often more of a wink: wining in a Burberry bikini in a living room with Shygirl; rapping about rolling Js with Rizla papers on a Honda motorcycle; cooing about the lonely mundanities of masturbation.

Similarly, Eusexua may not be immediately recognizable as whimsical; it initially sparks that same air of high-art seriousness that accompanies most of her work. This is partly because FKA Twigs is the multimedia art project that the 2020s demands, having consistently staked out innovative territory in the realms of dance, visuals, fashion, even advertising, right alongside her experimental pop. She apparently hopes to extend that project to the English language: “Eusexua” is her defining ethos, meant to reflect that spark of ingenuity—that quickening—in a moment of adrenaline. “Eusexua” itself is the union of “euphoria” and “sex,” and invokes the head-empty moment after orgasm, but it extends beyond the carnal. (And let’s be real, anyone inventing a word that practically requires a sensual chain-smoking accent has got to be a funny person.)

Eusexua is also an exercise in healing, a particularly potent concept given the years Twigs spent countering the alleged abuse of her actor ex-boyfriend. Because of that, and her ongoing lawsuit against him for sexual battery and emotional distress, the songs on Eusexua become saddled with a disturbing larger context—one that’s been interpreted as a vessel for her trauma. The video for “Perfect Stranger,” a 1990s-invoking house song about casual sex encounters, depicts Twigs in various scenes of domesticity and kink, including as a submissive swathed in latex. Kink is a common domain for some trauma survivors, and in one sense the video could be interpreted as a look at the healing process that can occur in slightly edgier sexual realms. The years after trauma often mandate a retreat—this is not a person surrendering, rather turning inward to figure out how to be reborn. Eusexua feels like that: a world built from Twigs’ most intimate thoughts, where she can imagine herself in dark club corners obscured by fog machines, anonymously flirting with danger. It suggests a sexual freedom but also an abnegation, a way for her to be someone else.

The album is fascinating in its stylistic choices, with future-forward tracks like “Drums of Death” bumping against older genres that make sense for her voice but might inspire trepidation for those of us who’ve lived through them already. The title track brings trance and trip-hop into the mix, which I do not love—perhaps the young Prague ravers who inspired Eusexua are further ahead of me on the 20-year nostalgia track, or maybe I just didn’t really like Ray of Light the first time around. The Eusexua experience, for me, is better embodied on a song like “Room of Fools,” with its motif of cascading synths and tinny house in a tense interplay with Twigs’ growl. Or on “Keep It, Hold It,” a diaristic tone-poem to external criticism and ennui on a bed of zero-gravity techno. Or on the standout “Striptease,” where she oscillates her voice like a body twirls on a pole, over a drum’n’bass thump.

Twigs has an elastic voice that soars in its high ranges; there is always a tension between the power of her physique and the diaphanous nature of her singing. (“I know I have this ethereal fragility, but actually I’m tough as nails,” she told Puja Patel in The New Yorker.) But that contradiction is a trick, too; her dance movements require grace and lightness, her vocals demand her ability to project operatically. It takes strength to be vulnerable, the paradox of the ages, so whether she’s dropping babyish coos on “Childlike Things” (with her 11-year-old collaborator, North West) or crooning rather despondently on “Sticky,” she’s manifesting the undercurrent of feminine power that unites her work.

It’s perfect that, after Twigs has hand-held us through this florid wonderland of her own spiritual rave, she walks us out with “Wanderlust.” The finale begins with her voice plain and unprocessed, with a minimally flanged guitar beneath her. It’s a proper denouement, like emerging from a warehouse club into the sunlight after a long night—a reprieve from the dark textures she’s explored throughout the rest of the album. “You’ve one life to live, do it freely,” she sings in a lovely and direct alto. “It’s your choice to break or believe it.” On paper it might come off as a platitude, but she lets it off like a mantra to conjure the quickening. Sex, too, is inherently pretty funny—sweaty and grunty and wild. It requires an eager willingness to embrace the awkward and make stupid-looking faces, a kind of impulsive choreography unto itself. And sometimes, the first instinct after an orgasm is to laugh, freely and without shame.