What ‘Sinners’ and Chelsea Reject Taught Me About the Power of Black Cultural Memory

Director Ryan Coogler’s Jim Crow-era horror-drama and a recent memorial show for a late Brooklyn rapper speak to how we honor legacy.

What is the responsibility of a griot? There’s always been more to the role than just singing songs for an audience. In West African culture, the griot is an orator, a cultural gatekeeper whose talents for song, dance, and storytelling are directly tied to their people’s history and well-being. A griot understands there’s no pain without pleasure, no reward without risk, and sifts through those raw feelings, pulling from the past and the future to make sense of the present. It’s in Gil-Scott Heron exposing a country more invested in space travel than accessible healthcare on “Whitey’s on the Moon,” or in Bbymutha’s triumphant reclaiming of the word “slut” from trifling baby daddies and schoolyard bullies on her 2020 song “Roaches Don’t Die.” The soul is in the details—griots, particularly across the Black diaspora, use lived experience and cultural touchstones to appeal to the spark that keeps the disenfranchised going, even when all hope seems to be lost.

This past weekend, the concept of the griot was on my mind. What should the relationship between a creative and their community be? How do we honor those brave enough to expose the ties that bind and stain our collective cultural consciousness through the power of music? Ryan Coogler’s latest film, the genre-bending horror-drama Sinners, turns the clock back to the Mississippi Delta in the 1930s looking for answers. Partly inspired by his late uncle’s love for blues music, Sinners channels complex thoughts on racism, capitalism, and religion through an ode to the power of Black musical connection across one long, hot day in the heart of the Jim Crow South.

Michael B. Jordan technically plays the lead as twins Elijah (“Smoke”) and Elias (“Stack”) Moore, rogue bootleggers returning home from Chicago to open a juke joint, but the film’s primary protagonist is their younger cousin and aspiring blues musician Sammie, portrayed by newcomer Miles Caton. We first see the character approaching the steps of his father Jedidiah’s church, bloodied and scarred and holding a busted guitar neck in his hand. “If you keep dancing with the devil, one day he’s gonna follow you home,” Jedidiah (played by Saul Williams) tells him a day earlier, seconds before he joins his older cousins in their scheming. We see the world through his passionate and naive eyes. He’s eager to get out from under the preacher’s shadow, to love up on girls and be ready to bust out a tune on his Dobro Cyclops resonator.

Two of Sinners’ most resonant scenes demonstrate how his raw skill takes him from being just a talented musician to a griot. As Club Juke’s opening night grows rowdier, Sammie takes the stage to perform the bruised love ballad “I Lied to You,” and his playing rips a hole in the space-time continuum. Suddenly, the aspect ratio changes and the camera begins wavering through the warehouse, surveying the ghosts of a musical past, present, and future. A Bootsy Collins-esque funk guitarist goes riff for riff with Sammie as the crowd, sweaty and lascivious, dances around them. A DJ dressed like he just walked out of Def Jam circa 1986 scratches records onstage while current-day rap fans twerk to that music. Captured with a glorious one-shot, it’s as pure and potent a display of musical communion as I’ve seen since Outkast’s 2006 jukebox musical Idlewild. The ancestors all float around the bar unseen, Black salvation and sin melting on the dancefloor, inspired by each other.

Aside from emphasizing the rich continuum of Black music, that charged and highly psychedelic scene is treated like its own religious experience. Christian iconography is everywhere throughout Sinners, but the blues is treated as a sensation even more organic to the Black experience. “[The blues] wasn’t forced on us like that religion was,” Delroy Lindo’s alcoholic piano player Delta Slim tells Sammie. The blues is treated as part of the same system of Black Southern roots as the hoodoo practices kept alive by Wunmi Mosaku’s Annie, ways to connect to, and even move between, the physical and spiritual realms.

It also acts as a beacon for the film’s sect of vampires, particularly their Irish leader, Remmick. Remmick and his two Klu Klux Klan-affiliated cronies spend much of their screen time playing Celtic folk music, first in an attempt to be invited into the club (they are vampires, after all) and then as a demonstration of sorts. Each converted soul adds to the vampire hive mind, their memories and talents absorbed into the collective. Remmick quickly recognizes Sammie’s gift for breaking through to the other side with the blues and wants it for himself, to commune with his own ancestors. The Irish step-dancing can only take them so far.

When we finally return to Sammie standing in church, guitar neck in hand and his father screaming “repent!,” he chooses the path of the bluesman—the griot of the era—and leaves Mississippi for good. The experiences of that night are a microcosm of the culture that raised him, and its bittersweet emotions—bonding with his cousins and experiencing his first love before everyone he knew was murdered by bloodsucking parasites—further fuel his pursuit of the blues. That responsibility, translating a town’s worth of pain and beauty into his guitar, is a heavy one, but it proves to be all the faith he needs.

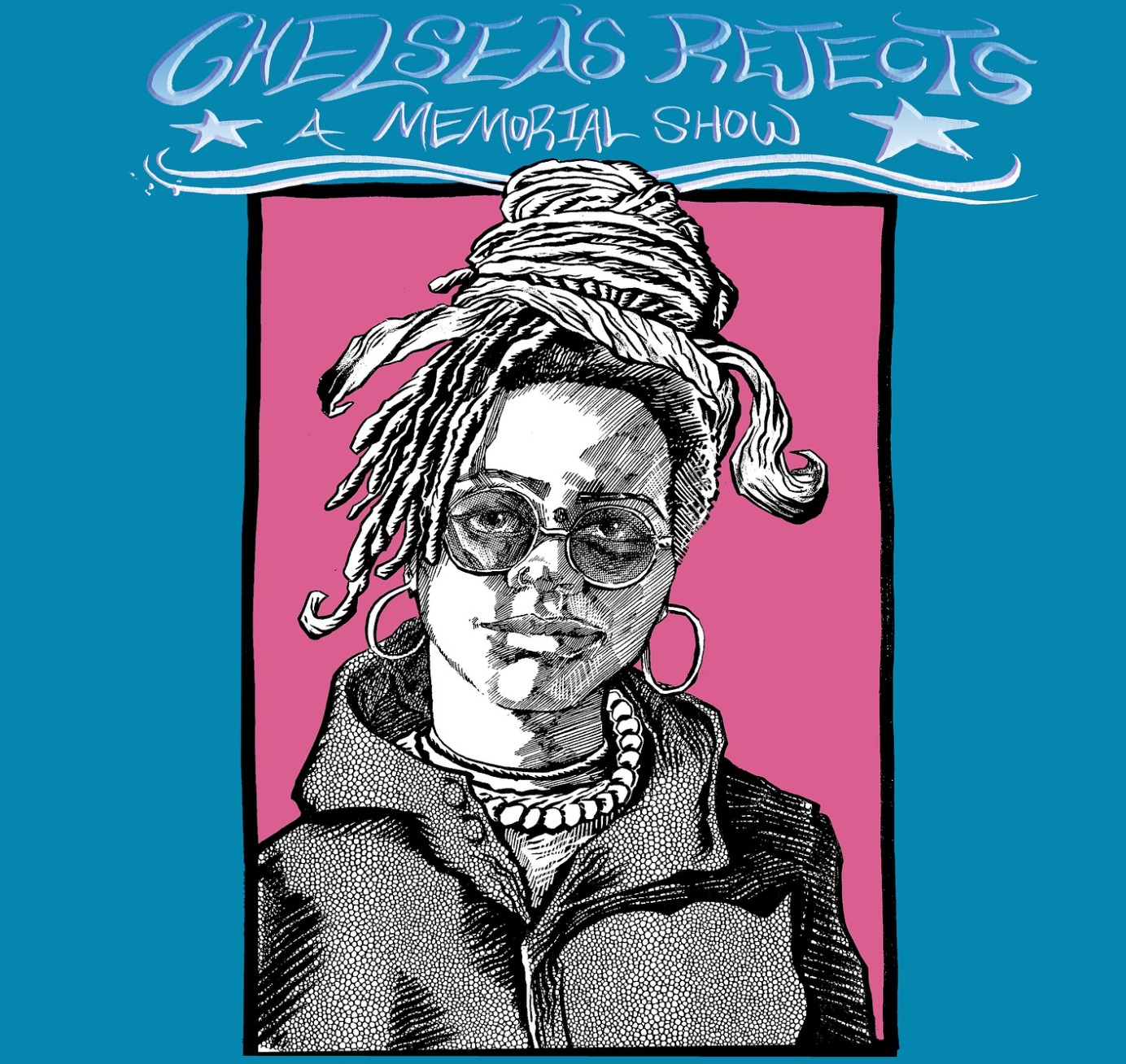

That message stuck with me as I made my way to a memorial show in Brooklyn two days later. Chelsea Reject, who passed away earlier this year at the age of 32, was being honored at the record and streetwear shop Loudmouth with an event called Chelsea’s Rejects, a showcase featuring friends and collaborators from the local indie rap scene. Though we weren’t close, I’d interviewed Chelsea a handful of times over the years and she proved to be as thoughtful and incisive as her music. She was a pioneer in her own right, becoming the first woman to release an album on legendary New York indie label Duck Down Records with 2015’s Cmplx, but she was also a mellow spirit dedicated to bringing people together under the banner of hip-hop, so her passing was a shock, to say the least.

There were few things Chelsea loved more than rapping with good friends and weed, and that spirit was felt the second I walked through the door. A $20 suggested donation came with a gift bag containing flowers, a print drawn by artist Virgil Warren and, of course, a pre-roll to burn during the show. Several people who took the stage that night mentioned how bizarre it was to be celebrating Chelsea’s life without her being physically present, but that didn’t stop these artists from fulfilling their roles as griots by conjuring her spirit. Every performer on the bill was connected to Chelsea in some way. Most came up with her in the scene at open mic nights and rap events, and that playful competitive spirit animated their sets. Buffalo rapper Dntwatchtv spilled about Chelsea’s constant words of motivation in between his bouts of fly shit. Both Brooklyn rapper Akai Solo and Brooklyn-via-Oakland rapper Nappy Nina reminisced on seeing her at open mic nights while they were still getting their feet wet.

The most powerful display of the night came from Atlanta rapper StaHHr, who was something of a mentor to Chelsea and her creative partner T’Nah. Many know StaHHr as a longtime collaborator of the late MF Doom, and her set put emphasis on the originals and remixes she created with the metal-faced villain. In keeping with the spirit of honoring the dead, she began her performance of the song “Celestial” by explicitly referencing the act of naming loved ones who’ve transitioned, a healing practice passed down from many African religions. She ended the song by listing the names of Black musical and literary icons who are no longer with us: Doom and fellow indie rappers Sean Price and Pumpkinhead; fallen L.A. rap emissary Nipsey Hussle and jazz icon Roy Ayers; writers bell hooks, Octavia Butler, and Nikki Giovanni; soul singer Angie Stone. One name stood out from the bunch, delivered in a slowed, impactful meter: Chelsea Lynn Alexander.

The loss truly hit me then—Chelsea was gone. Not forgotten, but a tacit memory floating through all our minds. I’ve lost quite a few friends and family members in my life, and as sad as I can get when thinking about phone numbers I can no longer call or DMs that will go unread, I’ve come to realize that these people live through us—our memories, our actions, our attitudes toward each other. Chelsea’s personality hit the sweet spot between playful and thoughtful, and the best way for me, for us, to honor that is to keep that vibe alive however possible.

In that moment, I was brought back to the ending of Sinners. There’s a 70-year time jump to 1992, where Sammie is now a veteran musician played by IRL blues icon Buddy Guy. He’s approached by Stack and Hailee Steinfeld’s Mary, the only two vampires who survived the attack and now live in cushy immortality. They offer to turn Sammie but he refuses, and Stack asks him to play a song on his acoustic guitar (“I never liked that digital shit”). Sammie’s intimate rendition of “This Little Light of Mine” briefly brings them back to a simpler time, when sunlight wasn’t deadly and trauma-bonding wasn’t the tie that binds them. For all the bad that came after, for all the loss and bloodshed, Sammie’s role as griot transmuted the story of that day into beautiful pain.

That same feeling spread through the audience at Chelsea’s memorial show. Rap and the blues are already distant cousins as is, but that night, much like Sammie, each of Chelsea’s Rejects did their best to turn grief and mourning into celebration. I don’t believe in an afterlife, but I, and several others, bore witness to the melancholy splendor of griots digging into their cultural bag to keep a memory alive.